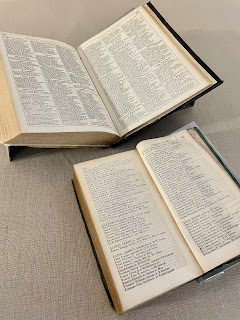

The Massachusetts Mercury was a tri-weekly newspaper, founded in 1793 and published once every three weeks by Alexander Young and Thomas Minns from their office on State Street in Boston. Following The Massachusetts Mercury through time can be a little confusing, as over the years it changed names numerous times and merged with other papers. Young and Minns were the publishers for several years and the paper was known as The Massachusetts Mercury until 1800 when its name changed to The Mercury and New-England Palladium. It was then known as The New-England Palladium from 1803 until 1814, followed by The New-England Palladium & Commercial Advertiser until 1840, when it merged with other newspapers to become The Boston Semi-Weekly Advertiser. At the time of the displayed 1796 publication, the nameplate included the Latin phrase “dulcique animos novitate tenebo” which one of our staff members was able to translate as “and I will possess an open mind towards unfamiliarity” which seems like a fitting motto for newspaper readers.

Since the volume is bound, it is displayed open to show both the last page of the May 24 edition and the front page of the June 21 edition. Because the paper was published only once every few weeks, the content spans a range of dates. The news section includes events that have occurred since the last printing, and the advertisements and notices of auctions are for upcoming dates weeks into the future. Looking closer at the content, the front page shows a surprising amount of information about ships, both listings of departure dates and destinations of passenger vessels, and advertisements to buy vessels, which emphasizes Boston's role as a port city. A fun detail is that each listing also includes a small etching of the ship mentioned! Beginning on the front page and continuing onto the interior pages are international and domestic news, with a heading reading "The foreign news in this day's Mercury will well reward an attentive person. The domestic news is all interesting." The last page is full advertisements, similar to the classified section of modern newspapers, along with a few marriage and death notices. The advertisements provide a glimpse into life in Boston at the end of the 18th century, letting us read first-hand about the types of goods and services that were offered. I've included an image below of an advertisement for watches and other jewelry.

As the Library’s Preservation Librarian, I love sharing items from our colonial newspaper collection as part of our outreach program, in part because they are often in remarkable condition given their age. Tour participants and social media followers are surprised to see items that are over two hundred years old in better condition than the 2004 Boston Globe that they saved to commemorate the Red Sox winning the World Series! We keep our newspapers in dark storage with controlled temperate and humidity, but the largest factor to their stable condition is that colonial newspapers were made of rag paper. Colonial paper was made from made from linen and cotton fibers or rags and is much more durable and stable than paper made from wood pulp and it doesn't become brittle or yellowed with age. It wasn’t a quick process, which is maybe why newspapers were only printed every three or four weeks!