|

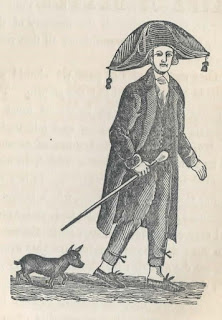

| Lord Timothy Dexter with his dog. From Kapp's biography |

To start, Timothy Dexter was not a Lord, it was a title he granted himself and this best sums up Dexter’s eccentric nature and grandiose self-image. Dexter was not originally from Newburyport and was from a very modest background. Born in Malden in 1743, Dexter received little formal education and apprenticed in a leather workshop. Always driven by his desire to make money and be part of high society, Dexter first made his fortune by buying Continental currency during the Revolutionary War. At the time, the new paper money held little to no value, but once the war ended, Congress was able to make good on the new money and Dexter amassed quite a fortune. We do not know if Dexter had the foresight to know this transaction would turn in his favor, but in any case this started Dexter’s string of “lucky” business dealings.

|

| Example of a bed-warmer. Via Digital Commonwealth |

With his fortunes, Dexter invested in his own mansion on Newburyport’s High Street. Dexter adorned the outside of his property with wooden statues resembling the nation’s leaders and prominent figures. In his Life of Lord Timothy Dexter, Dexter’s personal biographer, Samuel L. Knapp, writes “...in his rage for notoriety, created rows of columns, fifteen feet at least, high, on which to place colossal images carved in wood. Directly in front of the door of the house, on a Roman arch of great beauty and taste, stood General Washington in his military garb. On his left hand was Jefferson; on his right, Adams, uncovered, for he would suffer no one to be on the right of Washington with a hat on” (p. 25).

|

| View of Dexter's mansion and statues. Via Library of Congress |

|

| Punctuation page from "A Pickle" |

A lot can be said about Dexter’s eccentricities, but he was a noted benefactor to the town of Newburyport. He commissioned and bought a new bell for the town meeting house. He bequeathed a large donation to the town after his death and also to his native town of Malden. Newburyport accepted the donation with “gratitude and thankfulness” (Coffin, page 274). Dexter was known to partake in municipal matters such as being named a proprietor for the erection of the Essex Merrimack Bridge. See the 1791 Act Chapter 35 naming him as such.

All of Dexter’s odd endeavors have cemented him as a notable figure in the annals of North Shore history books. For more reading on the one and only Lord Dexter, see below:

- A sketch of the history of Newbury, Newburyport, and West Newbury, from 1635 to 1845

- Lord Timothy Dexter of Newburyport, Masstts. : first in the East, first in the West, and the greatest philosopher in the western world

- Timothy Dexter Revisited

- History of Newburyport, Mass. 1764-1905

- History of Newburyport : from the earliest settlement of the country to the present time : with a biographical appendix

- Life of Lord Timothy Dexter : with sketches of the eccentric characters that composed his associates, including his own writings, "Dexter's Pickle for the knowing ones

April Pascucci

Reference Librarian