The Robert Gould Shaw and 54th Massachusetts Regiment Memorial is one of the first stops for many Boston tourists, prominently placed on the edge of the Boston Common facing the Massachusetts State House. Since its unveiling in 1897, it has commemorated Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, the first federal black regiment of soldiers from a northern state during the Civil War. Interestingly, this monument has been edited throughout its history as new generations considered how and who it was commemorating.

|

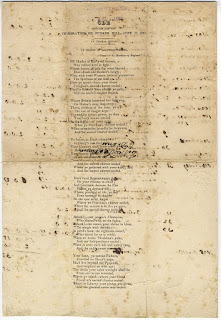

| Postcard published Mason Bros. & Co. Boston, Mass. ca. 1907-1917. |

The 54th Massachusetts Regiment was the result of recruitment of African-American soldiers following the Emancipation Proclamation. While state troops such as the 1st Kansas Colored Infantry existed before the Emancipation Proclamation, the 54th was the first federally sanctioned black regiment in the Union Army. But who would lead this regiment? Massachusetts Governor John Albion Andrew specifically chose Robert Gould Shaw, who was from a prominent Boston family who were passionate abolitionists. Shaw was promoted to Colonel specifically so he could take command of the new regiment. Throughout the north, prominent black abolitionists like Frederick Douglass (whose son Lewis would serve in the 54th as a sergeant) and Martin Robinson Delany (who would later become the first African-American field grade officer in the U.S. Army) promoted the recruitment effort, and as a result soldiers from across the northern regions, and even as far away as the Caribbean, came to join the 54th. Despite issues regarding full pay and material support, so many came to volunteer that the 54th was soon full, and the Union Army commissioned the 55th Massachusetts Regiment so that more black soldiers could enlist.

The 54th Massachusetts Regiment was mustered into federal service in May 1863, and fought in their first battle at Grimball's Landing in July. They would also go on to fight in the Battle of Fort Wagner, during which almost half of the regiment was wounded, captured, or killed. Colonel Shaw was among those killed during the attack. Despite or perhaps because of these horrific causalities, this battle would cement the valor of the 54th Massachusetts Regiment. Sergeant William Harvey Carney, who had joined the regiment after escaping from slavery, would later win the Congressional Medal of Honor for his gallantry in saving the regimental colors when the original flag bearer fell.

The 54th continued to fight under different commanders, including Col. Alfred S. Hartwell, whose

papers reside at the State Library of Massachusetts. They were disbanded in August 1865, several months after the official end of the Civil War. At the end of the war, surviving members of the 54th Regiment, veterans of other black regiments, and the black community of Beaufort, South Carolina wished to create a memorial to the historic regiment near Fort Wagner, but the area and the hostility from the local white population dissuaded this idea. A second chance for a memorial was born in a meeting at the Massachusetts State House months after the end of the war, involving Governor Andrew, prominent anti-slavery U.S. Senator Charles Sumner, abolitionist Samuel G. Howe, and other Boston politicians and abolitionists regarding a memorial to Robert Gould Shaw. However, this effort stalled when several of these men passed away soon after. But the project was reinvigorated by Joshua Bowen Smith, a prominent caterer and state representative of African and Native American ancestry who had previously worked aiding fugitive slaves as part of the Underground Railroad and the Boston Vigilance Committee. Smith helped to raise nearly $7000, the equivalent of about $168,000 in modern currency, before his death in 1879. By 1883, the project was back on track and the accumulated funds raised through private donations had reached $17,000 (about $407,000 today) and work on the memorial officially began (

The monument to Robert Gould Shaw, 1897).

According to a contemporary account, the concept of the memorial came from Charles Sumner, who envisioned “a statue of Colonel Shaw mounted, in high relief upon a large bronze tablet” (

The monument to Robert Gould Shaw, 1897). Augustus St. Gaudens was suggested by renown architect H. H. Richardson to be the artist of this monument, and he was contracted for the work of an equestrian statue of Shaw, which was cast in plaster in 1883. However, Shaw’s family “was acutely conscious both of the historical significance of the regiment's formation and of the fact that their son had been a mere colonel. So they asked the sculptor to show Shaw ‘bound together’ in common cause with his men” (Smee, 2014). While originally intended to be a memorial specifically to Shaw, it became the first soldiers’ monument to honor a group rather than an individual (Galvin, 1982).

St. Gaudens would work on the sculpture for nearly 14 years and hired forty men to serve as the models for the soldiers’ faces. St. Gaudens said that he considered it his duty to memorialize the soldiers “in a noble and dignified fashion worthy of their great service” (Galvin, 1982). On May 31, 1897, the sculpture was unveiled with high ceremony to high praise. The bronze cast showed Colonel Shaw astride his horse, with twenty-three black soldiers marching in line behind him, with more troops suggested by lines of rifles in the background. Above the soldiers is an angel, holding an olive branch (symbolizing peace) and poppies (symbolizing death). “Look at the monument and rend the story… the mingling of elements which the sculptor’s genius has brought so vividly before the eye” wrote one reporter for the Boston Globe. The surviving members of the 54th Massachusetts and their descendants were honored guests in the parade leading to the memorial.

|

| Postcard published by Valentine and Sons Co. New York. ca. 1907-1909. |

The marble base and terrace of the memorial, designed by architect Charles F. McKim, included inscriptions written by Charles W. Eliot honoring both “The White Officers” and “The Black Rank and File.” However, only the white officers of the regiment that died alongside Colonel Shaw at the Battle of Fort Wagner are listed on the back of the marble terrace. The black soldiers were left completely anonymous. In the early 1980’s, some wished to correct this omission and inscribe the names of the black soldiers who died in the Battle of Fort Wagner. Spearheading this project, which would include a full restoration of the memorial, was John D. O’Bryant, the president of the Boston School Committee at the time and the first African-American to be elected to said committee. However, some objected to the addition of the names, citing that the omission in the original memorial “should serve as a reminder of the racial prejudice that had characterized the late nineteenth century” (Whitfield, 1987). However, further research found that Colonel Shaw’s sister wrote a letter in which she vehemently expressed the desire that the names of the black soldiers should be on the monument “in order to leave no excuse for the feeling that it is only men with rich relations and friends who can have monuments” (Whitfield, 1987). Therefore, in 1982, the names of 62 soldiers who also died at the Battle of Fort Wagner were added to the monument.

In 2014, the Massachusetts Historical Society curated an exhibit called “Tell It with Pride: The 54th Massachusetts Regiment and Augustus Saint-Gaudens’ Shaw Memorial,” which showcased the individual stories and photographic portraits of many of the soldiers that fought in the famous regiment. You can

see many of these portraits still on their website. You can also see portraits of soldiers

in the 55th Massachusetts Regiment on Flickr as part of the State Library’s digitized Alfred Stedman Hartwell collection.

Unknown Soldier from the 55th Massachusetts Regiment. Photograph is part of the Alfred Stedman Hartwell collection at the State Library of Massachusetts.

Currently, the monument is undergoing further restoration which began earlier this year. This planned restoration, which will take about six months, will involve the removal of the monument and the construction of a new concrete foundation at its base. In the meantime, an

app providing more information about Robert Gould Shaw, the 54th Massachusetts Regiment, and their role in the Civil War will be available to anyone looking to learn more about this unique and important monument.

Further Reading:

- Galvin, John T. “The Magnificent Saint-Gaudens.” Boston Globe. December 26, 1982.

- Smee, Sebastian. “A closer look at the storied 54th.” Boston Globe. May 4, 2014.

- Sweeny, Emily. “Civil War memorial across from State House will be taken down for major face lift.” Boston Globe. October 15, 2019.

- Whitfield, Stephen J. “Sacred in History and in Art": The Shaw Memorial.” New England Quarterly, 60 (1). March 1987.

- The Monument to Robert Gould Shaw: Its Inception, Completion and Unveiling, 1865-1897 (1897): https://books.google.com/books?id=jBnneVg34oIC&source=gbs_book_other_versions

- Massachusetts Historical Society, 54th Regiment! http://www.masshist.org/online/54thregiment/index.php

- National Park Service, Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Regiment: https://www.nps.gov/boaf/learn/historyculture/shaw.htm

Alexandra Bernson

Reference Staff