James Bowdoin was elected as governor in May 1785, following John Hancock’s resignation partway through his term. Once in office, Bowdoin worked to collect back taxes, which Hancock had been reluctant to actively pursue while governor. But in a depressed post-Revolutionary War economy, Bowdoin made it a priority to both raise taxes and collect back taxes in an effort to raise funds for the state’s portion of foreign debt payments to European war investors. This was met by protest from those in the central and western parts of the state who were struggling financially since they had not been paid for their wartime service. Individuals now found themselves having to pay high taxes that they could not afford, or risk losing their livelihood, a situation that caused unrest and ultimately led to what we now know of as Shays’ Rebellion.

This month marks 235 years since the conclusion of Shays’ Rebellion, which was an armed uprising that occurred in western Massachusetts beginning in the summer of 1786. Residents of the area organized protests in response to the fact that the legislature had adjourned without addressing their concerns about taxation. From August to October, groups of protesters successfully forced the closure of courts in Northampton, Worcester, Great Barrington, Concord, and Taunton. In January 1787, led in part by Daniel Shays, groups of protesters organized in an attempt to overtake an armory in Springfield. They were met by a militia organized by Gov. Bowdoin, which consisted primarily of individuals from the eastern part of the state. Clashes continued from the end of January into early February, before the protesters’ forces fell apart and many participants fled north.

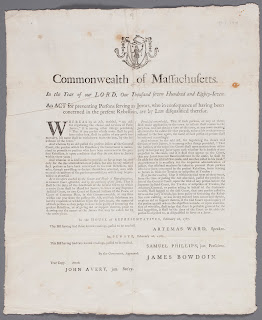

The broadside in our collection was Issued by the General Court in the weeks after Shays’ Rebellion. The Act printed on it stated that anyone who favored the rebellion, or gave aid or support to the rebellion, was prohibited from serving as a juror for three years. Selectmen from the towns in which the participants resided were instructed to remove their names from the jury-boxes (from which names would be drawn to serve as jurors). Earlier in February, the legislature also passed the Disqualification Act, which disqualified any known participant in the rebellion to serve in some elected or appointed positions. There is a lot more to the economic climate leading to Shays’ Rebellion, the rebellion itself, and its aftermath than we can address in this blog post. To learn more, check your local library for books like Shays's Rebellion: Authority and Distress in Post-Revolutionary America by Sean Condon and Shay’s Rebellion: The American Revolution's Final Battle by Leonard L. Richards.

And lastly, a note on the condition of this broadside, since it looks pretty good for having been printed 235 years ago! We do a lot of collection repair and preservation work in-house, but we send items out to the Northeast Document Conservation Center (NEDCC) for more involved work. In 2018, this broadside was one of a few that underwent treatment at NEDCC. It was removed from its plastic enclosure and then cleaned to reduce staining, discoloration, and acidity. It was also humidified so the edges could be uncurled and creases reduced, and then any tears and losses were mended with thin Japanese paper and wheat starch. Check out the image to the right to see how it looked before treatment and compare that with the “after” photo featured at the beginning of this post!Elizabeth Roscio

Preservation Librarian